Diameter Signaling Security – Protecting 4G Networks

To date, almost all of the conversations regarding security of mobile networks in the media have focused on the SS7 protocol. While this system is the backbone of mobile network, and handles roaming and control of mobile subscribers using it , it is gradually being (very slowly) supplanted by the Diameter protocol, which is used for control for LTE/4G networks and subscribers.

What’s the Question?

So far the conversation around Diameter has primarily revolved about attacks that are possible in theory – including some potential attack research to which we contributed to. While this is useful, and does show that Diameter networks are indeed vulnerable, just being vulnerable is not enough to know the extent of the real danger. Within security, to truly assess the risk of an event, we need to take into account whether a threat actually exists, and that is done by various forms of the following formula:

- Vulnerability x Cost x Threat = Risk

So while the of a Diameter network is clear from the preceding research, and the (of an attack) is easy to determine – ranging from information loss up to communication interception location tracking all the way up to the Denial of service of a mobile network – the actual real so far is not known. That is because up until today no information has been released on Diameter attacks seen “in the wild”. That’s what we are going to change.

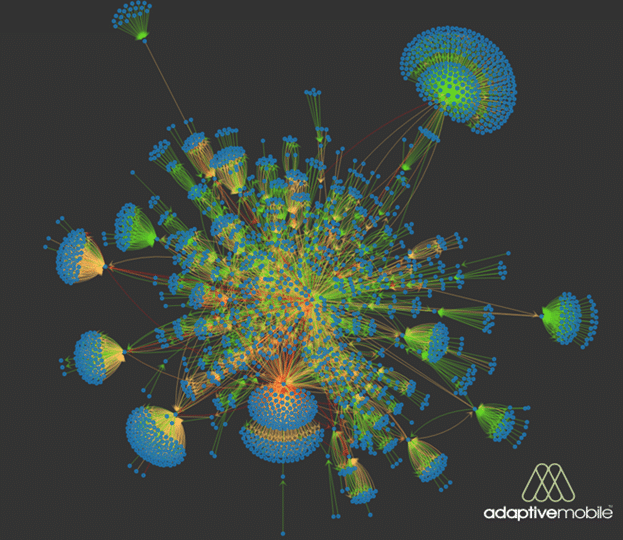

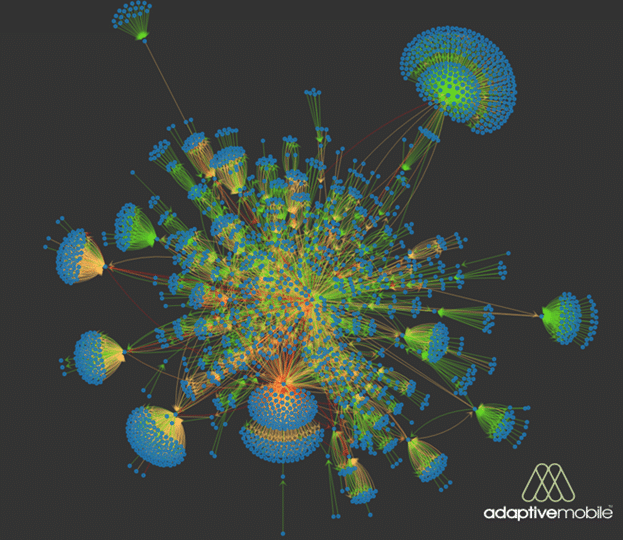

Visualisation of International Diameter traffic over multiple 4G Networks

Late last year we analysed sample traffic from over half a dozen Carriers’ international Diameter traffic around the same time span. This involved traffic to / from 80+ countries in all 5 continents, although the majority of traffic was from the Americas & Europe. Within this traffic we searched for traffic based on specific types of suspicious activity, which are classed by the GSM Association into different types, and found that around 3% of traffic exhibited anomalies based on these types. Interestingly this percentage is actually quite high compared to SS7 , however while these categories and percentages are useful as a benchmark, they are misleading as they don’t tell you anything about whether the traffic is actually malicious or not, which is critical in understanding the real threat.

After subsequent investigation, we believe the vast majority of the above to be either misconfigured network elements, mistakes in setup, or random spurious events – not malicious events. But of the above we did find a small amount of suspicious/malicious activity over Diameter, which did answer what we wanted to know, was Diameter being exploited? to which the answer seems to be yes. What was surprising was its complexity and level of advancement, and strangely, how few malicious cases there were compared to SS7 (more on this later).

A Random Walk

In one particular suspicious/malicious case, we observed very sophisticated attempts to potentially test the Diameter defences in place in one operator. Over a period of roughly one hour a customer network received incoming Authentication-Information-Requests (AIR) and Update-Location-Request Diameter packets from multiple sources, all concerning the same mobile phone subscriber. ULR packets are used to change the designated location of a subscriber, while AIR packets normally precede ULR and is part of the procedure of authenticating a subscriber when it roams to a new network.

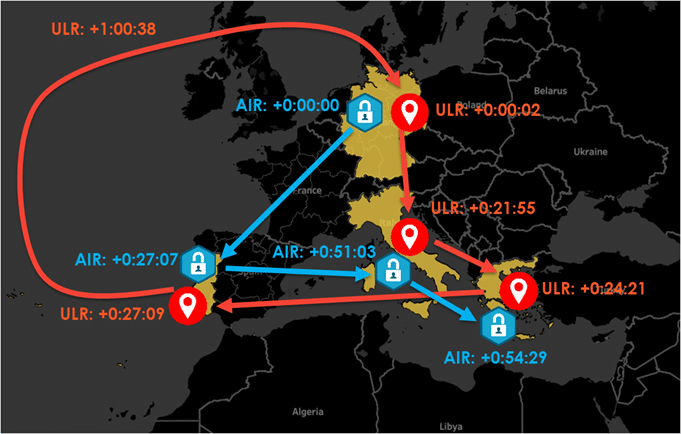

Suspicious Activity Timeline/Location Map

The sequence of events is shown in the map above, with the times in hours:minutes:seconds. The algorithms built into our Diameter Network Protection Platform detected that not only was the subscriber moving at implausible speeds – AIR and ULR packets were begin received from new countries faster than a subscriber could reasonably be expected to be present, we also saw that authentication and update locations requests were out of sequence and came from different countries. For example, at time +0:54:29, an AIR was received from Greece for the subscriber, indicating the subscriber was trying to authenticate to a Greek mobile network, but just over 5 minutes later at +1:00:38, an ULR packet was received from Germany – indicating the subscriber was attempting to register its location in Germany. Other similar implausible transitons and AIR<>ULR deviations could also be seen at other times.

One of the reasons an attacker would attempt to do this – change the designated location of a subscriber to a fake location – would normally be so they can intercept subsequent communications to a subscriber. This is the attack method that was executed by a criminal group against German banking customers over SS7 in early 2017. However in this case we did not see this (SMS interception) attempted, instead its probable that this activity was designed to simply see was our customer network vulnerable to complex attacks over Diameter, and that the source countries were very likely spoofed.

Where are the Attacks?

So what does all of this mean? Well this type of attack (spoofing the location of a subscriber) is quite complex and difficult to execute, but it is very powerful as it allows the attacker to then perform several different types of attacks. This behaviour was one of many suspicious/malicious activities that we saw on Diameter networks, and the overall conclusion we took from that is that we proved that attacks over Diameter do happen. But one other thing we also observed is that the rates of strongly suspicious/malicious activity that we see seems to be much lower in Diameter than in SS7.

The question then asked would be why. The strong, and we believe main reason, is because of usefulness of the Diameter network to conduct signalling attacks, compared to SS7. Simply put, Diameter is still far less used than SS7. To demonstrate this, for one of our Mobile Operator customer, we examined a representative sample of their SS7 and Diameter traffic (around 10 minutes in the busiest time of the day) and we found that in this period their SS7 Traffic came from over 200 countries, but over Diameter it was less than 100 countries.

But even this hides the number of active nodes on these networks – in this time period the number of unique endpoints over SS7 was 16 times more than Diameter. So logically it makes logical sense that an attacker is more likely to use SS7, because the range of targets they can attack is wider, i.e. every country in the world.

A less important reason as to why we don’t see as many attacks over Diameter is access. It is probably harder for an attacker to get access to Diameter, as the number of countries using it is lower, and more importantly there is not yet a multitude of smaller MVNOs, and other legacy companies connected to the Diameter network, unlike in SS7 which has built up far more entities connected to it than was every envisaged, rendering its trusted network model obsolete.

Summing Up

All being said this should not be seen as an indication though that Diameter is safer, because inevitably as SS7 Security improves, and Diameter use widens and eventually starts to replace SS7, we expect malicious misuse of Diameter networks to increase. Right now attackers seem primarily to be testing what can be done over Diameter networks, and how operators are vulnerable, with the bulk of exploitation of signalling networks remaining over the SS7 network. That won’t stay like that forever, and with the eventual greater uptake and access to the Diameter network that will occur, we can expect the bulk of the attacks to start to transition over to the Diameter network over time. In order for Mobile Operators to answer the question of Network Security, they will have to make sure that they are prepared to identify and block attacks over the Diameter network.